Depending on the stream of classical Christian education one has been trained in, Mortimer Adler’s work could be foundational, moderately common, and relatively obscure. Adler himself only came to faith in God late in life, but he spent much of his life defending the classical tradition and pushing towards a classical education for every child.

In the Paideia Program (1984), a work by Adler and his colleagues with the Paideia Group, the authors discuss three kinds of teaching and learning. In chapter one, Adler and Charles Van Doren consider the conduct of seminars. In chapter two, Theodore Sizer talks about academic coaching. And in chapter three, Adler sets forth principles for didactic instruction. A few years later, Adler wrote an essay in the The Paideia Bulletin (May 1987) called “The Three Columns Revisited” (then included in his 1988 edition of Reforming Education: The Opening of the American Mind) in which he returned to these three types of teaching and gave particular attention to the nature and practice of the Socratic seminar.

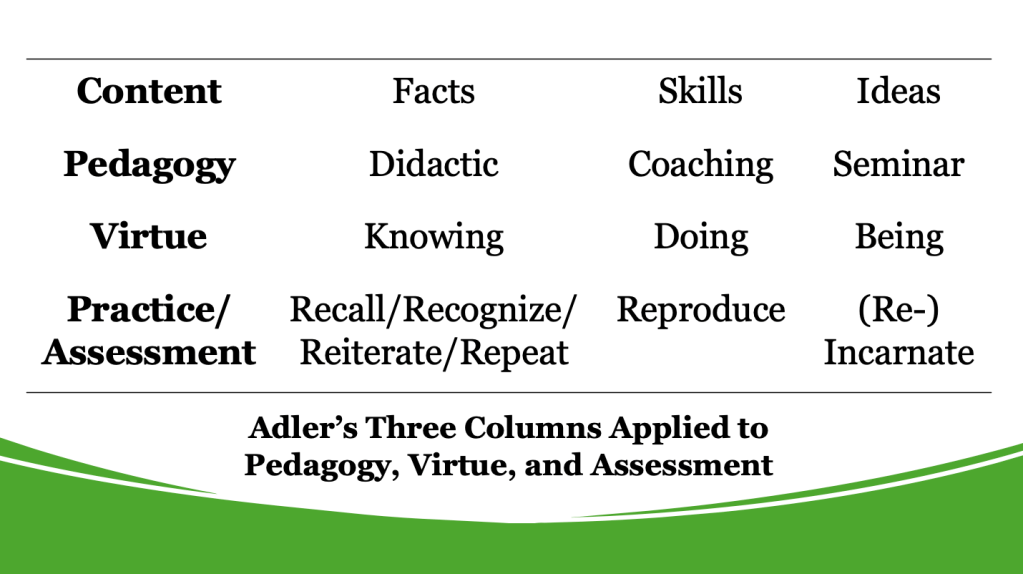

I have revisited Adler’s revisitation of the three columns many times. At the core of his proposal is that students learn not only facts, but also skills and ideas, and each of these three correspond best to one of the three modes of teaching. Facts, he proposes, are best taught by didactic instruction (i.e., lecture). Skills, he then asserts, are best taught by academic coaching. Finally, ideas are best taught by means of Socratic seminar. This proposal of three types of teaching for the core lessons of facts, skills, and ideas has been a huge help to my own teaching.

However, the more I’ve considered these three columns of teaching (pedagogies) and three aspects of learning (facts, skills, and ideas, I see that one can take them even further. So, as I’ve revisited Adler’s revisitation, I want to propose a couple more rows to his three columns.

In an excellent book entitled Beauty in the Word, Stratford Caldecott makes the following claim: “Too often we have not been educating our humanity. We have been educating ourselves for doing rather than for being” (11). I would add that most education aims even lower–for merely knowing. Knowing is, indeed, a necessary part of education. In an age of Google searches, many don’t find it valuable to memorize any information, assuming they can always look it up. Knowing relates to facts, and facts do serve as a foundational aspect of learning. But it goes deeper. Beyond the facts that we know stand the skills that we can do. Doing things well (e.g., the skills of rhetoric, writing, logic, etc.) is a valuable part of education, too. But doing, like knowing, is not the end. The heart of classical Christian education is formation, not merely information, so knowing and doing must give way to being. We want students to be (or become) certain kinds of people. Ideas are the corresponding content to our aspirational virtue of being.

Finally, we want to know how we can practice facts, skills, and ideas to make them more ingrained. It turns out, the practice of these things is also the same means by which we can assess them. We practice and assess facts by means of recall, recognition, reiteration, or repetition. We practice and assess skills by means of reproduction. And we practice and assess ideas by means of (re-) incarnation, our ability to give flesh to these ideas in the real world.

Adler’s work has been an incredibly beneficial source for my own thinking, teaching, and growth as a teacher and human. I hope you take the time to read his excellent ideas, and I hope my brief thoughts prove helpful in putting Adler’s work into practice in your own classroom.